“I’m not saying I can smell fear, but that’s just because I’m very modest.”

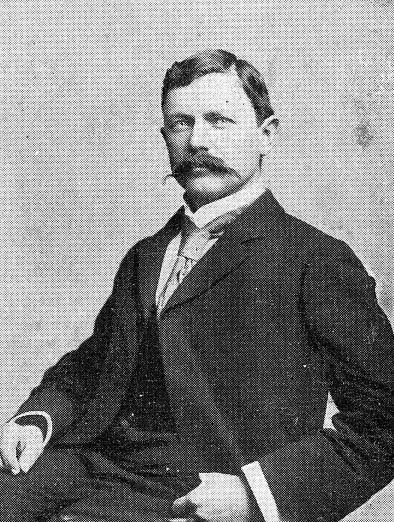

~Frederick Russell Burnham

The Boy Scouts of America have been around since 1910, and in that time they have made quite an impression on the nation. Some of you might associate Boy Scouts with your childhood, earning merit badges and going camping and learning how to like, tie knots? That’s a thing you did right? Others of you, like our staff, might also associate Boy Scouts with their childhood, only the focus is more on that one kid in your High School that really stuck with it, and while it was cool that he got to use a pocket knife and shit, he always wore knee-high socks with shorts and you know definitively that he did not get laid until he was well into his 20s. And still others of you might think of the Boy Scouts as an organization that is not particularly good at being nice to gay people.

But, something that almost no America thinks about in relation to the Boy Scouts are the men responsible for for the very idea of scouting itself. Scouting was first established in the United Kingdom by Robert Baden-Powell in 1907 as a way to support youth physical, mental and spiritual development. As you likely know, this goal was achieved through the focus on outdoor and survival skills, with the notion that a self-reliant child with a diverse skill set would be able to use what they learned through scouting and apply it to take constructive roles in society.

Now, “going outside” isn’t something that we really like doing much ourselves, and since we live in the age of the internet we don’t have to. But in the pre-internet age of the early 1900s when this all started, we imagine that going out and learning how to make fires and whittle sticks into shivs (we’re assuming that’s a thing Boy Scouts did) was probably both constructive and about as exciting of an activity as you could get. Either way, it’s an influential movement, and though it was started by a Brit, it was in fact inspired by an American man who basically taught Baden-Powell everything he knew. A tiny man with a powerful nose who you probably haven’t heard of, which is a right we’re going to wrong. Because there were few Americans as badass as…

Frederick Russell Burnham: America’s Scout

Frederick Burnham was born on May 11th,1861 on a Lakota Sioux Indian reservation in Minnesota which, if our theory on Indian burial grounds holds true, means that he was instantly imbued with supernatural powers. His father, Edwin Otway Burnham, was a Presbyterian minister and missionary, while his mother, Rebecca Russell Burnham moved to Iowa from England at the age of three, and randomly went to school with Buffalo Bill. When he was an infant (he claims to have been two in his book, Scouting on Two Continents, but the facts say he was…well, probably like, 18 months old) he was inadvertently swept up in the Dakota War of 1862. During the war, a group of Sioux warriors attacked the town of New Ulm, Minnesota, which directly neighbored their home. While Burnham’s father had gone to a different town to buy ammunition, his mother saw a troop of Native Americans in war paint approaching her cabin. She figured that if she stayed, both she and Frederick would be killed, while also knowing that she would not be able to escape quickly enough if she was trying to carry her child. So, she jammed the infant Frederick inside a bunch of green corn, figuring that it was green enough to not catch fire if the house went up in flames, hoped that the baby would make a point to shut the hell up, and made a break for it, running six miles in a surprisingly short time and leaving her baby in the fucking dust. Well, more like in the ashes- when she got to safety she turned around and saw that, yup, her house was on fire.

Maybe she was being a shitty mother, or maybe she knew that her son was destined to be one of the best Americans ever at surviving impossible situations, but when she came back the next day with armed neighbors, she found Frederick Russell Burnham alive in her burned down house, nestled in a basket and surrounded by singed corn. In Burnham’s own words, “She found me, as she often loved to tell, blinking quietly up at her from the safe depths of the green shock where I had faithfully carried out my first orders of silent obedience.” If you’re thinking this is some superhero origin story shit right here at this point, we’d probably have to agree with you.

We’re just saying, we see some similarities here.

To top it all off, for someone practically born into a war between Native Americans and settlers, he had a remarkably progressive view towards native populations for someone living in a time where the government paid for Indian scalps, saying at one point, “To-day recalling all the crimes of the Indians, which were black enough, one cannot but cast up in their behalf the long column of wrongs and grievances they suffered at the hands of the whites.” Ah, it’s so nice to not have to write about a bigot when writing about a person from the 19th and early 20th century.

He moved to Iowa for the early part of his youth, where he met Blanche Blick, the woman he would later end up marrying. His family then moved to California in 1870, hoping that it would help his father recover from an accident he had while trying to repair their home (a tree fell on him and crushed his lungs to the point he was spitting blood), and it was there at the age of 10 that he first found himself getting shot at, which he said, “Made a very vivid impression on my boyish mind” because Frederick Burnham really was a fan of understatement. In 1873, his father passed away, having never recovered from, you know, having a damn tree dropped on him by a vengeful God, and while his mother and younger brother took a loan of $125 from a friend in Los Angeles to go back East and take lodging with one of his uncles, Frederick decided to stay in California so he could work, support himself, and help repay his mother and brother’s debt.

He was 13 years old at this point.

In comparison, when you were 13 you were either vigilantly hiding unwanted boners or involved in some Machiavellian scheme to ruin the social life of a former best friend.

He spent the next few years working as a mounted messenger for Western Union, primarily riding in California and Arizona where he at one point had his horse stolen by Tiburcio Vásquez, a relatively famous bandito. Burnham’s response to finding the horse had been stolen was to sprint as fast as he could for two miles to try to cut the horse thieves off—which he almost did, missing them by just five minutes before resignedly walking to the nearest camp. Vásquez was captured only a few months later, and the 14-year-old Burnham visited him in jail to give him a piece of his mind for stealing his horse. Vásquez responded by apologizing to the kid, saying he’d not have taken the horse if he had known it belonged to Burnham, and as way of apology he gave Burnham his horse to ride (he wouldn’t be needing it because he was about to come down with a real strong case of “execution by hanging”), which Burnham proudly rode around Los Angeles for a time.

Burnham, through his childhood growing up around Native Americans and his experience on the frontier, had long had an interest in scouting (well, as much as he could at 14) and he left the Western Union to serve as a scout and Indian tracker in the Apache Wars. During his adventures, he met an old scout named Lee, who taught him various detecting methods, including how to spot Apache camps as far as six miles away by simply smelling the scent of burning mescal (which Apaches would roast and pat out into cakes for nourishment) through a Wolverine-like sense of smell and a knowledge of the air currents of the canyons they traveled through. Again, this is some super powers shit we’re dealing with.

By the time he hit 18, he had fully grown into his frame, which was only five feet and four inches. His small stature and boyish features never really did go away, though he would be able to use that to his advantage down the line. Burnham had learned much out on the frontier, receiving advice from Al Sieber, the Chief of Scouts, among others, but his skills were ultimately solidified through a mentorship he had with an old man known by Holmes. Holmes had served with great scouts such as John C. Fremont and Kit Carson (it’s okay we’ve not heard of them either) but was old and impaired, though with a sharp mind. He had a lifetime of scouting experience and frontier knowledge that he was desperate to pass on to some younger generation, as his entire family had been lost in the Indian wars.

No, wrong Holmes.

Holmes and Burnham traveled together for some six months, where Holmes taught the young Burnham the “right way” to perform hundreds of tasks, all in exhaustive detail. They went over topics as varied as the proper tying of ropes to finding water in the desert, and by Burnham’s estimation, the things he learned from Holmes actively saved his life in situations where he would have otherwise perished. The two of them earned a living by hunting and prospecting, while Burnham took side jobs as a cowboy, a guard for mines, and a scout. After they parted ways, he spent time in Globe, Arizona, where he befriended a the Gordon and Wells families, who happened to have been mixed up on the losing side of a the Pleasant Valley War. Fred Wells in particular took in Burnham as a member of his family, and trained the 19-year-old Burnham how to shoot.

The Pleasant Valley War, and Burnham’s attempt to escape it, was a dangerous time in the young scout’s life. His decision to support Fred Wells and his son John led to a bounty being put on his head. Though they didn’t know his name, he was described as an “unknown gunman” with a “Remington six-shooter belt.” He knew he had to get out of the conflict, as his only stake was his friendship to the Wells (who themselves weren’t even members of the two primary feuding families in the war) and with a price on his head, Globe, Arizona was no longer safe. He attempted seek help from his friend Judge Aaron Hackney, the editor of the Arizona Silver Belt, who could hopefully him escape, but on the way he was nearly killed by a well-known bounty hunter named George Dixon.

While briefly hiding in a cave, Dixon came across Burnham, put a gun to his head, and ordered him outside. However, before he could execute his bounty, Dixon was shot and killed by a White Mountain Apache named Coyotero, who had been tracking the man because of crimes he had committed against his tribe. And since life sometimes takes its cues directly from a terse Quentin Tarantino standoff, Burnham’s response to the slaying of his captor was to dive, grab his rifle, and kill Coyotero himself. We can’t confirm that he stood, panting, covered in blood screaming, “WHAT JUST FUCKING HAPPENED” immediately afterwards (in fact we are almost certain he didn’t), but we can confirm that we would have reacted that way.

Artist’s rendition

He managed to reach Hackney, who helped him establish various aliases and escape to Tombstone, Arizona. On the way he ran into a smuggler named Neil McLeod, who was with his severely injured brother, who had a bounty on his head. Burnham, instead of attempting to collect the bounty himself, he agreed to help McLeod find shelter for his brother, and the two of them made way to Tombstone. In Tombstone, Burnham became a well-known prizefighter, and a successful smugger along the Arizona-Mexico frontier at the behest of his new friend McLeod. In 1882, however, McLeod was killed accidentally by his own men. Burnham was deeply affected by this, saying in his memoir, “McLeod’s grip on the heartstrings is not loosened by lapse of years or death” but with his closest connection to Tombstone gone, he decided to leave.

The rest of 1882 saw Burnham attempting to track Geronimo during the Apache Wars before spending the next few years going to California to attend high school (he never graduated), serving as a Deputy Sherriff of Pinal County in Arizona, and generally eking out a living herding cattle and prospecting. When he was 23, he went back to Prescott, Iowa, to visit Blanche, his childhood sweetheart, and married her on February 6th, 1884. She would follow him on many of his adventures from then on out, proving to be capable with a gun herself.

Not pictured—a sawed-off Colt resting on her lap.

He and his new bride moved into a house with an orange grove in Pasadena, where his mother and 14-year-old brother, who must have felt like a slacker in comparison, joined him. It didn’t take long for him to tire with the life of an orange farmer (by his own admission, he was absolutely lousy at it), and while he continued to work around the West for the next nine years, the frontier had long been tamed, and didn’t offer any real challenge to a man of Burnham’s talents. With that, his focus turned to southern Africa, where the Dutch and English were, well, basically being assholes to the native populations while fighting amongst themselves. Burnham was particularly fascinated by the work of Cecil Rhodes, who at the time was working to build a railway across Africa (the Cape to Cairo Railway) and at 31, figuring himself to be at the height of his physical prowess, he sold off the remainder of his possessions and went to Durban, South Africa with his wife and son.

Burnham and his family began marching to meet with Rhodes at Matabeleland, and by the time he reached his destination the First Matabele War had broken out between the British South Africa Company and the Matabele leader, King Lobengula. He immediately signed up to be a scout and joined the fighting, going on patrols to find Lobengula, who had burned down his own royal town and fled at the onset of the war. The most notable event to occur to Burnham during this extremely lopsided war (there were 750 British and 1000 Tswana troops suffering about 100 casualties, while the Matabele, or Ndebele, had 80,000 spearmen, 20,000 riflemen, and had over 10,000 casualties) occurred in the Shangani Patrol, the one notable Matabele victory in the war, and the third time (or so, we’ve sort of lost track) that Burnham escaped nearly certain death.

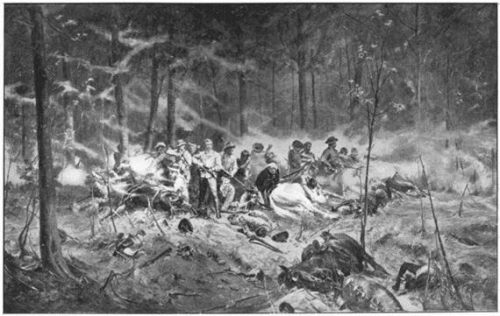

Pictured above: somewhere you definitely do not want to be.

The Shangani Patrol, or Wilson’s Patrol, involved 37 British South Africa Company soldiers under the leadership of Major Allan Wilson who just so happened to find themselves surrounded against 3,000 Matabele warriors. This occurred partly due to some bad tactics by the British South Africa Company’s military leadership (the group that originally was small enough to flee individually became too large to escape and too small to fight when the reinforcements they asked for ended up being just 21 men) and because, well, they fell for a trap. Major Wilson’s initial patrol ran into a group of Matabele women and children who claimed to know where Lobengula was, and instead of saying, “Hmmm they could be lying” he just fucking went for it. At the same time, the Shangani River had flooded the area, making it impossible to escape. In desperation, Wilson sent Burnham and two other men to cross the River, evade the enemy troops, and procure more reinforcements. Now, we’ve been saying that Frederick Russell Burnham is a badass, but no matter how badass he was, this was absolutely the only reason he survived that day. If a different rider had been selected, his story would have ended in what is now Zimbabwe.

Burnham and his two fellow riders avoided a stream of spears and bullets, making it to the main force just in time to see them engaged in battle as well. While taking up arms with the larger group of troops, Burnham said to Major Patrick Forbes, who decided that there was way they could send more reinforcements to Wilson, “I think I may say that we are the sole survivors of that party.” Every last member of the Shangani Patrol, outside of Burnham and the two that rode with him, were killed, though it’s estimated that they killed between 400 and 500 of their enemy, and they were hailed as national heroes in both England and Rhodesia for a time.

There have been rumblings by revisionist historians that Burnham wasn’t sent, and instead just deserted his troops, but we’re not really going to acknowledge that because the evidence for it is sketchy at best, and also because Frederick Burnham was a badass and was not the type to desert.

Plus, he’s on record with saying shit like this.

Despite this setback (well setback isn’t the most comfortable word to use there—this was all very blatant, pretty oppressive imperialism going on here) the British South Africa Company emerged victorious (helped by the fact that Lobengula ended up dying of smallpox). The war only lasted from October 1893 to January 1894, but with its completion Burnham was awarded the British South Africa Company Medal, a gold watch, and a 30 acre tract of land in Matabeleland (which almost immediately after formally became Rhodesia, named after Cecil Rhodes.) The next year, while still in Rhodesia, Burnham led the Northern Territories British South Africa Exploration Company, where he discovered major copper deposits in North-Eastern Rhodesia, which apparently was good enough to earn him a fellowship at the Royal Geographical Society.

Peaceably looking for copper wasn’t going to last forever, partly because Frederick Russell Burnham was always eager to join a fight, but actually because England was kind of in full Evil Empire mode at this stage in history, and in 1896 the Matabele rose up against the British South Africa Company again in the Second Matabele War, which was pretty much the same as the first, a little bit louder, and a little bit worse. The Mlimo of the Ndebele, their spiritual leader, was believed to have stirred up anger against the British South Africa Company, and his call for battle came right as many of the troops in Rhodesia were preoccupied in fights elsewhere. As a result, the British weren’t able to send enough troops to decisively end the war, and it waged on for 19 months, costing 400 lives from the British South Africa Company and, ugh, holy shit, 50,000 Ndebele and Shona casualties. Goddamn it history, you’re kind of a killhappy bastard sometimes aren’t you?

*Meekly waves banner* yayyy history…

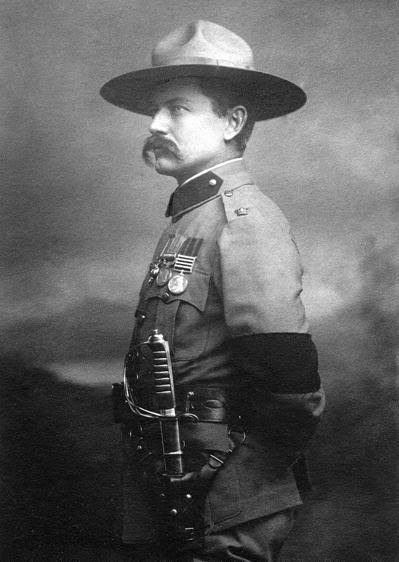

Burnham met Robert Baden-Powell during the Second Matabeleland War, where Burnham, now officially the Chief of Scouts for the entire British South Africa Company, pretty much taught him everything he knew, from woodcraft to how to travel in unfamiliar land without use of a compass or a map. Baden-Powell was so impressed with Burnham that not only did he steal most of these lessons to incorporate into his books on Scouting (first 1899’s Aids to Scouting and later 1908’s Scouting for Boys) but he also started to wear a Stetson with a neckerchief and adopt it as his signature look (again, basically stealing it from Burnham, who had been rocking that for years).

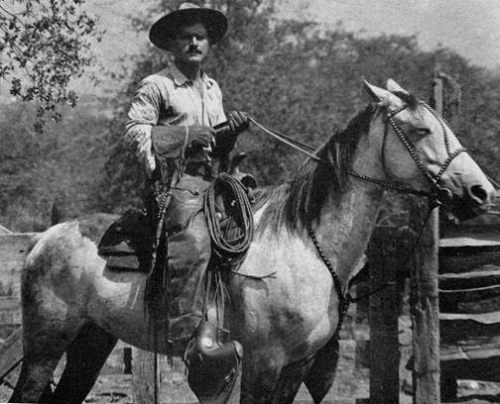

And rocking it with aplomb.

Burnham didn’t particularly mind, as he was a modest man who didn’t care to brag about his accomplishments, and generally supported the idea of teaching children scouting techniques, probably for the same reason why his mentor Holmes was so determined to teach him. When, eventually, scouting made it to the United States, he became a big supporter of it, and befriended many involved in the Scouting movement. That might not be particularly noteworthy, except for the fact that the Chief Scout Citizen of the United States was Teddy fucking Roosevelt.

Now, before we get into Burnham’s most notable action during the Second Matabele War, we’d like to give you this quote from Teddy Roosevelt himself, because you’re going to need some good will to get over this next part. “I know Burnham. He is a scout and a hunter of courage and ability, a man totally without fear, a sure shot, and a fighter. He is the ideal scout, and when enlisted in the military service of any country he is bound to be of the greatest benefit.” Pretty cool, right?

Now let’s talk about the time he assassinated a 60 year old man.

Oh, story time!

Now, Frederick Burnham did not get out of the Second Matabele War particularly unscathed—in 1894, his wife gave birth to his second child, a daughter name Nada, who was the first white child to be born in Bulawayo. Her name came from the Zulu word for lily. Unfortunately, Bulawayo was also the site of the most successful siege by the Matabele army, and she died of fever and starvation during the attack early in the war. Burnham pretty much placed all the blame for this on Mlimo, who was considered the central figure leading these armies (though, as it turns out, he probably wasn’t—he was just an old sorcerer who gave warriors “potions” to make them immune to bullets, but it was easier for the Brits to focus their anger on a single figure).

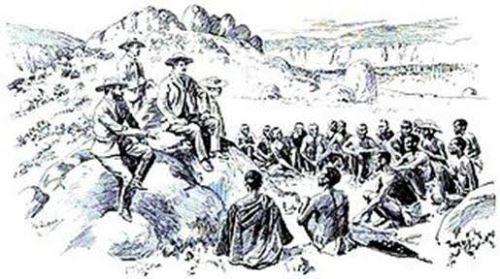

So it was assumed that the quickest way to end the war was to cut off the opposition’s head, the head in this case being Mlimo. Burnham, with the help of an unnamed Zulu informant, was able to find the secret cave where Mlimo was hiding, which was directly adjacent to a small village of 100 or so huts, mostly filled with warriors. He was told to bring in Mlimo, preferably alive, but dead if absolutely necessary. At this point, Burnham and another soldier snuck in and waited for Mlimo to enter and start his dance of immunity (we’re pretty sure it was a dance meant to make him immune to bullets, but holy shit how crappy would it be if that was the equivalent of a white flag?) at which point Burnham straight up shot the dude in the heart and the two scrambled the fuck away before any of the nearby warriors could chase after them.

…Actual artistic representation.

To be fair to Burnham, this actually did basically end the war. There still remains questions today if this guy was the Mlimo or just some random old man who got shot for no reason, but word of the assassination was enough to let Cecil Rhodes walk into a Nbebele stronghold and demand that their warriors lay down their arms, which they did, thus ending the war. So…good job Burnham? Yay?

Anyway, though his role in the assassination was eventually officially investigated by the British, nothing came of it, and as soon as the war ended Burnham took his family back to California, and from there he and his 12-year-old son Rockerick went off to the Yukon to prospect in the Klondike Gold Rush, but he didn’t stay very long. First, the Spanish-American War broke out, and he rushed to join the fight only to arrive just as the war had ended (Teddy Roosevelt made a point in a book he wrote to bemoan the fact that Burnham wasn’t able to fight along his side) but, due to the end of the 19th century being all lopsided wars, all the time, he rushed off to fight in the Second Boer War between England, the Orange Free State, and the South African Republic.

And holy shit was Burnham ready to get his war on again. When he received a message from Lord Frederick Roberts, offering him a position as Chief of Scouts for the British in the war, he was…let’s just say enthusiastic. We’ll just describe it in his own words. “At that message, all the gold of the Klondike was no more to me than to the frozen monsters whose tombs we had thawed to obtain it. Within an hour, I was on my way to Africa.”

To be fair, if we were in a place filled with frozen monster tombs, we’d want to get out too.

Dunham was given a command post and the British Army rank of captain, and he got to work spending most of his time behind enemy lines to gather information on blowing up railway bridges and tracks. While his previous war experience had left him previously unscathed to the point that you might be wondering that, combined with his “as a baby he survived a night in a burning house and came out unscathed” history that he might be invincible, the Second Boer War had him on the ropes on several occasions.

First, during the fighting at Sanna’s Post in March of 1900, he managed to get captured by Orange Free State troops. Now the battle itself was a mess for the British—155 of their 2,000 troops ended up dead or wounded, 428 were taken prisoner, and they lost seven guns, while the fortified force of 400 Orange Free State soldiers only saw three dead and five wounded among their casualties. However, the clusterfuck of this battle had nothing to do with Burnham getting captured—he gave himself up as a prisoner on purpose, so he could obtain more information on the enemy. Once he got the information he needed, he slipped his guard, and spent the next two days on the run before meeting up again with the British army.

Shortly thereafter, he was again captured, this time trying to warn British troops of an ambush. He was spotted by Boer soldiers behind enemy lines, and knowing that escape was impossible he allowed himself to be taken prisoner, while immediately plotting his escape. While he lied about his identity, some of his captors suspected he might be Frederick Burnham, which would make him an extremely valuable prisoner, and one who would be put under heavy guard. An intelligence officer questioned him, and decided that he was not Burnham—as Burnham described it, “[H]is card index of personal characteristics was a bit off. I was supposed to be a most ruthless character, born in the extreme Wild West of America and familiar with Indian warfare—my favorite practice of scalping being but a slight index to my general ferocity.”

So basically, he managed to convince them he wasn’t himself because his reputation led everyone to believe that he was just going to start scalping people left and right.

Frederick Russell Burnham, pictured left

Frederick Russell Burnham, pictured right

Safe from the scrutiny his notoriety would have brought him, he feigned an injury to his knee, limping heavily and groaning in pain. This placed him in a wagon with wounded officers, which was not very heavily guarded. After a few days of biding his time, he waited for evening, where he dropped himself between the two wheels of the wagon, falling between the legs of the oxen. He let the cart pass him before running for a few miles. During the daytime, as he was stuck in a wide open veld where he could be spotted from miles away by Boer scouts, he found a 4 inch trench that he lay in, face down and motionless until nighttime, when he would run as far as he could. It took him four days of repeating this before he could find the British lines again, and he subsided only on one biscuit and an ear of corn throughout this whole time (he was actually annoyed that he even had the corn, because it would stick out of his pocket and he feared that it would be enough to get him spotted during the days where he basically was playing the most high stakes game of hide-and-seek imaginable).

And finally, his last engagement of note, and indeed his last engagement of the war itself, saw him wounded during the British march on Pretoria in June of 1900. During a skirmish, Burnham had his horse shot out from under him. The dead horse pinned him to the ground and knocked him unconscious, though no Boer soldiers checked on him to see if he had been injured or killed. He woke up several hours later in enough pain that he feared he had broken his back. He managed to eventually get up and find cover, and seeing a farmhouse he considered turning himself in for capture and medical attention, until he started to vomit blood. By that point, he shrugged and thought, “Welp, I guess I’m going to die soon,” so he wrote a letter to his wife and took a nap.

When he came to, he felt stronger and, looking around, he found the distillery of Esterferbraaken, an important spot along the railroad that he was supposed to destroy. So, still injured, he snuck in during religious services and blew up the railroad line at two places using the twenty-five pounds of guncotton he had on him. He crawled to an empty animal enclosure to avoid capture during the aftermath, where he stayed for two days and nights, still greatly in pain. He did not have a drop of food or drink during this three day ordeal. When he finally managed to find a lull in patrols to escape, he crawled out and, hearing fighting in the distance, went toward the battle, where he was found by a British patrol. Surgeons in Pretoria examined him to find that he had torn apart his stomach muscles and burst a blood-vessel—if he had tried to eat or drink anything, it probably would have killed him. Still, his injuries were quite severe and life threatening, and Lord Roberts ordered him to be sent to England for medical help.

We suspect he didn’t exactly feel like traveling by horse this time around.

In England, he was promoted to major, commanded to dine with Queen Victoria just a few months before her death, and was later presented (this time by King Edward VII) the Queen’s South Africa Medal and the cross of the Distinguished Service Order, the second highest decoration in the British Army. His rank was made permanent, but he did not go back to war, and in fact his fighting days had officially come to an end. He went on an expedition through the Gold Coast (present day Ghana) in 1901 working for the Wa Syndicate in a search for minerals and improved river navigation, and from 1902 to 1904 he worked with the East Africa Syndicate, looking for mineable mineral deposits in Kenya. Afterwards, he returned to North America, spending several years in Mexico—first, he worked with the Yaqui River irrigation project, attempting to make a damn to enrich the valley (which he had conveniently purchased some 300 acres in for speculation), while going on a handful of expeditions that included the founding of Mayan ruins, including the Esperanza Stone.

Oh. Neat.

He did, in 1909, take a job overseeing a private security detail of 250 men for a summit in Mexico between President William Howard Taft and Porfirio Díaz, the president of Mexico where he managed to discover a would-be assassin carrying a palm pistol and subdued him before the two presidents could cross his path. By 1910, he was back in America, lobbying Congress to pass a bill in favor of importing hippopotamuses to America as a food source. He actually was lobbying along with Captain Fritz Joubert Duquesne, which was hilarious because during the Boer War, both Duquesne and Burnham were under orders to assassinate each other. Duquesne was a lifelong spy (who would eventually go to jail in America for spying for the Nazis) who had a begrudging respect for Burnham. Burnham didn’t have any hard feelings for Duquesne’s whole “trying to assassinate him” thing either, saying at one point, “He was one of the craftiest men I ever met…he would be the last man I should choose to meet in a dark room for a finish fight armed only with knives.”

Now, we should take a moment to talk about the hippopotamus scheme, since you definitely did not wake up today assuming you would read the words “hippopotamus” and “scheme” placed together, but here you go. In 1910, America was facing a food shortage, so Robert Broussard, a Louisiana Congressman, decided that wetlands and swamps could be converted into farms for hippos, since it’s fairly similar to their current habit. How he came up with hippos specifically, we have no idea, but he also realized that these hungry hungry water mammals could probably eat up water hyacinth, an invasive species Louisiana was having an issue with. If you’re wondering, yes, apparently hippo meat actually tastes really good. Obviously, nothing eventually came out of this—the logistics of transporting hippos from Africa to America to farm was pretty difficult, but it was even more difficult to figure out the logistics of shipping the meat after they had been slaughtered. But, for a time, Frederick Burnham was working with his mortal enemy to try to bring hippo meat to the American public, which is fairly amazing.

Though it’s probably for the best that this plan fell through.

When World War I broke out, Teddy Roosevelt tapped Burnham and 17 other officers to raise a volunteer infantry division to serve in France in 1917 as soon as America entered the war. He went about setting up a regiment that was similar in structure to the Rough Riders, but nothing came of it because President Woodrow Wilson refused to use any of the soldiers. This of course pissed Teddy Roosevelt (who was against Wilson’s earlier neutrality position) and after he disbanded the volunteers, he wrote and published The Foes Of Our Own Household, which basically was 360 pages of Roosevelt brutally bashing the sitting President (which, coupled with a series of relentless political attacks, is credited with helping the Republican Party regain control of Congress in 1918).

Since he couldn’t fight in World War I, he spent most of his time in California actively doing counterespionage work for Britain, mostly pitted against Fritz Joubert Duquesne. The two of them mostly kept each other at bay, and still maintained their mutual respect for each other—in 1933, Duquesne was quoted saying, “To my friendly enemy, Major Frederick Russell Burnham, the greatest scout of the world, whose eyes were that of an Empire. I once craved the honour of killing him, but failing that, I extend my heartiest admiration.”

After the war, Burnham, who despite his travels and speculations never had much in the way of wealth, struck oil on his land near Carson, California in 1923. He funneled about a quarter of the oil into the Burnham Exploration Company, a syndicate he created in 1919 with his son and a few friends. The company managed to pay out $10 million in dividends in its first ten years, and he was able to spend his later life in comfort.

Artist’s rendition of Frederick Burnham striking oil.

He spent his later years working as a conservationist. In 1914 he had helped established the Wild Life Protective League of America, but after striking rich he helped found what would become the World Conservation Union. He also an original member of the California State Parks Commission, a founding member of the Save-the-Redwoods League, and in his old age was the president of the Southwest Museum of Los Angeles, and the Honorary President of the Arizona Boy Scouts. He spent the rest of his life in California—his wife passed away after a stroke in 1939 at the age of 77 and after 55 years of marriage, and he followed suit in 1947, dying of heart failure at the age of 86, which in “spent half of your adult life actively looking for wars to fight” years is roughly 320.

Now, Frederick Russell Burnham’s legacy lies in the Scouting movement he helped influence, and in the thousands of quotations made by notable historical figures about him (since he was not one to brag about himself). Sir H. Rider Haggard, inventor of the lost world literary genre, described Burnham once by saying, “Burnham in real life is more interesting than any of my heroes of romance” which seems like a good enough legacy to leave behind.

So we salute you, Frederick Russell Burnham. As the Boy Scouts always say, “Way to kick ass so much, guy who inspired us!” Full disclosure no one in our staff was ever a Boy Scout, so that might not be a thing they say. But we’d like to think it is.

A very colorful account synopsis of my grandfather’s life. Some of the language would probably make him blush, and some parents of modern scouts would probably faint if little Tommy heard such things, but myself believes your words capture the feelings in the moment perfectly! This was a very fun fact read! By the way, the man on the horse was my Dad! Thank you. Frederick Russell Burnham II

This might be the best comment we’ve ever gotten on this site.